A dawn stalk for deer provides the perfect opportunity to experience offal the way it should be – fresh from the beast and cooked to perfection

The movement of the muntjac buck can first be seen in the half-light. However, we have to wait for the pre-dawn grey to relinquish its grip, finally revealing the verdant green of the valley below, before we can catch sight of him once more. The buck at last emerges from cover, bold and brassy, fortuitously pausing, framed between thick clumps of bramble. When it comes, the shot momentarily shatters the silence of dawn but the birds soon resume their song – cautiously to begin with, then building to a cacophony as the sun breaks beyond the eastern treeline.

Flora Phillips aims to change the way we think about cooking and eating offal

Mayfair butcher

Deer management is most often a solitary pursuit but today I have company. Flora Phillips, better known as Flossy to her friends and growing number of enthusiastic followers on Instagram (@floffal), is somewhat of a force of nature. For her day job she works as an artisan butcher in a wholecarcass butchery in Mayfair. Beyond this she is a passionate advocate for nose-to-tail eating, meat provenance and a champion for her interest in and love of offal. And this is to be her first stalk; her first animal taken from field to fork. (Find The Field’s venison recipes here.)

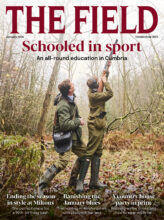

Resting his rifle on sticks, the writer prepares for the shot – a swift and humane despatch is always the goal

We walk cautiously to the shot site, soon finding the buck lying where he had last stood. We examine where the round has entered and exited, passing through the vitals and resulting in a swift and humane despatch. Phillips runs her hand over the emerging summer coat as I explain the process to come. When the trigger is pulled the work starts: the deer has died to provide, she feels an added ethical and perhaps even spiritual requirement to make the most from all that the animal gives. She credits her mother with encouraging her early adventures in food, supporting her natural curiosity for the new or innovative. It was an 11-year-old Phillips who first cooked and ate a sweet lamb’s liver, a transformative event that started her culinary journey.

Perhaps it is this innate challenge of the orthodox and her natural artistic ability that took her first to study history of art and then on to run a gallery. Something was missing, however, and she was drawn to return to the creative medium of food, and meat in particular, finally channelling this by joining an elite but growing band of female artisan butchers who have broken into this largely male-dominated sector and are busy making it their own.

Offal requires care and understanding in the preparation and the cooking, but the results are more than worth the effort

Cooking venison offal

We light the charcoal in a safe clearing and pick bright-green, young wild garlic leaves from the expansive beds that follow the course of the stream, close to where the buck had fallen. While the coals smoulder, Phillips delicately lays the offal on a wooden board and begins her work. The Oxford English Dictionary tells us the word entered the English language from the Dutch afval, derived from af (off) and vallen (to fall), literally ‘the bits that fall off’. Since then, the British relationship with offal has largely been going the same way.

Lowly origins

This aversion is not exclusively British but our predilection to snobbishness may come into play, for the concept of offal is tainted by lowly historic origins. In medieval times, ‘umble pie’ was made from deer innards, or ‘numbles’, and was the reserve of peasants. This eventually jumped to ‘humble pie’ and is the source of the commonly used term ‘eating humble pie’. Hardly a positive advertisement.

Further denigration of offal followed the advent of slaughterhouses in Britain in the 18th century. What resulted was somewhat of a revolution, in meat terms at least, as it suddenly became more available to greater sections of society. There was an abundance of offal that was prone to rapidly go off and could not be easily preserved or transported. The solution was to offer it to the poor, with institutions being built adjacent to the slaughterhouses for this very purpose. The association seems to have left an indelible legacy on the psyche of the vast majority of the British public: offal as unwanted, second-rate, even sinister.

Yet the denizens of the 19th-century country houses gave offal a certain glossiness. There, Edwardian breakfast tables positively groaned under the weight of devilled kidneys and the traditional after-dinner savoury kept piquant liver at its heart, too. While the connotations eating offal may have changed, it became both rarefied, eaten by the upper classes in their homes and clubs, and commonplace, such as the tripe eaten by the working classes but shunned by the increasing majority in the middle.

Adding wild garlic

“We have become so accustomed to meat meaning muscle. Because of this we are missing so much variety, so many raw materials and different flavours,” Phillips explains, running her knife smoothly through the raw liver and cutting two fine slivers before unceremoniously placing one in her mouth and offering me the remainder. With some trepidation I take the piece and begin to chew. There is not the strong, gamey, bloody flavour I expected but something altogether finer, headier, at once sweet yet powerful. “Many people are put off in their childhood, being served overcooked and strong liver – soon everything just tastes the same,” she remarks. “Offal is delicate but complex; it needs care and understanding. But the important step is to try it with an open mind.”

Nutrient dense

Eating the whole animal is nothing new. The offal, or all the non-muscular edible parts of the carcass, is the highest nutrient- dense part of the animal but also the quickest to perish in the elements. Early hunter-gatherers venerated offal above all, and sought to eat these nutritious parts first and preserve the longer-lasting meat with smoking or salting for later. This practice has largely failed to transcend to most modern hunting practices but remnants can still be found. In the UK few still perform the tradition of eating the ‘stalker’s breakfast’, where the liver is cooked, fresh and still warm from the beast, on return from the hill or wood. Phillips thinks this is a shame and shows me why.

To the hot skillet she adds smoked back bacon from the nearby farm shop, a diced home-grown onion and a bunch of the freshly picked wild garlic. The liver is seared, caramelised and rested before being plated together. Her hands move in the controlled rhythms of the trained chef: exacting, caring. After plating, she adds flecks of wild garlic flower before we sit to eat in the spring sunshine. There is smoke and richness, the salt of bacon, the sweetness of the fat and the long, heady flavour of the liver, so far away from the grey homogeny of distant school-meal memories.

A keen advocate for nose-to-tail eating

“Venison offal is my favourite. Eating it is an event, bringing the wild into the kitchen. It is evocative and truly special,” Phillips confirms before starting work on the next dish, finely trimming the heart free of the tough fibrous parts, leaving fine pink muscle. She recreates her signature dish: muntjac heart carpaccio, beetroot and burnt onion ketchup with foraged wild garlic buds. We are now sharing in a culinary journey of the deer’s organs but each as if visited for the first time, each a new adventure. With the heart one is immediately overwhelmed by the sense of ‘clean’. The firm, fine flesh only hints of venison, with no gamey aftertaste: it is a revelation.

“Butchery is an art form. It is choreographed, physical, as you work in and around the carcass,” she insists as kidneys sizzle on the glowing coals. “But working with offal is even more immersive. It can be such a sensory overload; the texture, the feeling, the smell, even the sound as you run your knife through it. Really, it is because I am taking something so overlooked and celebrating it, showing all its beauty.” We go on to sample venison kidney, carrottop pesto, rhubarb and whisky compote, dripped with wild garlic oil. There is sweet and sharp against the savoury of the kidney that absolutely nothing else could imitate. It is a dish to convert even the sceptic.

Phillips is studying what I do as much as I am learning from her. Although she works daily with carcasses, this is the first time she has seen the death of the animal, the first link in the chain. We walk the wood line and a broad pastured valley while we wait for dusk and our next stalk. I show her the browse line and the woodland damage, and we talk about the need to manage deer numbers to protect the vulnerable habitat. We speak of harvesting deer, of a source of quality, high-welfare meat that is both ethical and sustainable. But I do not sidestep the truth: the process necessitates killing. “I feel what I do honours the animal; it keeps that connection to it being a living being,” she says. “To me, it is a responsibility to use all we can, to eat it all.”

The cycle continues

The gloaming is fast descending as we stalk a valley edge, glassing the treelines and tussocky meadows that roll gently away from us. The cull plan has a single roe doe remaining and we duly find a yearling emerging beside a rough copse. Navigating the dead ground we come into position above her and I rest on my sticks. As the cross hairs naturally fall behind the shoulder, I subconsciously control my breathing and the shot is away. The last doe of the season drops where she stands, marking the completion of another cull year. Shortly we are beside the beast and beginning the process once more. We talk of our experience as we work, of what it meant. Another cycle. The same as so many before, yet now somehow different.