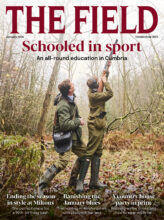

An attempt at the feat of a sporting lifetime is filled with highs and lows. However, whether congratulations or commiserations are in order at day’s end, the journey is truly unforgettable writes Sam Rickitt.

Unlike Buchan’s protagonists in John Macnab, this sporting adventure has its origins in an excess of ebullience rather than ennui. At the Countryside Day held at Cheltenham last year, a fine lunch crossed with a winning horse produced a successful bid in the Countryside Alliance auction. These charity fundraisers are often fertile ground for fieldsports fun yet prizes too frequently languish forgotten until the time to claim has passed. This time, post-auction ennui did not take hold. (Enter The Field’s 2025 Macnab Challenge here.)

It is north to Invermark, part of the Dalhousie estate in Angus, that this merrily-won Macnab attempt takes me on a dank autumnal day. Covering 55,000 acres with heather-clad moors, salmon fishing on the North Esk and a deer forest established in 1853, Invermark is eminently suited to the challenge. Headkeeper Gary Maclennan has been at the estate for 12 years and is an enthusiastic proponent of the Macnab. “It’s a great way to test our clients’ abilities to the limit,” he explains, “and is a challenge for us as much as our guests. They may be good with a shotgun but not as practised with a rod or vice versa. I find it really rewarding when we bag the part of the challenge they think they will struggle with most. Or after starting at daylight, we finally land a salmon or shoot a grouse just before dusk.”

A dreich morning on the river

My guide for the day is beatkeeper and stalker James Fairlie, who has worked at Invermark for three years, and before this spent 10 years on an estate near Inverness. Though he is an accomplished angler – I’m regaled with a fishy tale of catching a 10-pound salmon on a 3wt rod – his true passion is the hill. Fairlie is unequivocal as to which quarry should be first: “Absolutely the salmon.” The estate has four miles of river at Edzell and four miles of Invermark fishing. He explains the running order for the river: “We are starting at Lyn Martin, a good producing pool, fishing into Island – great but better in higher water – and then on to White Water, which has a more difficult cast.” His confidence is reassuring and helps mollify the concerns I’ve had about the fish ever since accepting the challenge.

The river is a short hop from our dawn rendezvous at the Spar in Edzell, and we brave a downpour to don waders and get rods ready. It takes a few casts to settle in but what could be better than Spey casting for salmon on a Scottish river – apart from perhaps being on the hill or a grouse moor. I work my way downstream through the pools but unfortunately the only thing catching my hook is wet autumn leaves, so after an hour here we move on. We walk to White Water through native woodland thick with leaf litter. The bank sits high above the river, and tree branches make an inviting target for my fly. As we arrive a salmon leaps from the water, a thrilling reminder that they do lurk beneath, but after 40 minutes Fairlie calls time. I am worried about leaving the river with a fish unclaimed but the dreich weather means a mist lurks on the hilltops, and he fears the hill will be even trickier. “The stag may well be the hardest part,” he suggests, and we can return to thrashing the water once beast and brace have been accounted for.

Ready for the hill

With the morning already almost over, we meet the rest of the stalking team and gulp a cup of coffee at the estate office as Fairlie collects the rifle. One of the team, Karen da Rosa, has been coming to Invermark for 10 seasons with her eclectic range of dogs. “It is going to be a dark day,” she observes. “You could see rifle sparks by three o’clock yesterday.” She helps on the hill but her real calling is working her dogs on a driven day: “I have springers and a teckel, a mastiff wolfhound and labradors. Dogs have been my passion since I was a teenager.”

The estate rifle is a .270 Win Tikka T3x with Kahles scope, and after a successful test on the requisite iron target, we venture westwards into Glen Lee in a collection of 4x4s. (Read The Field’s advice on how to choose the best rifles.) Fairlie lays out the plan of action. “We are going to the south beat, which is mine and 10 minutes from here past the loch,” he says. “No one else is out today, however, so we can go elsewhere if needed.”

Spotting deer

Hidden by the mist, a stag roars in the distance. “We may hear them,” Fairlie declares, “but on a day like today when the light is poor they can be a devil to see.” On the crags of Craig Maskeldie, Fairlie spots a small herd grazing among bright-orange targets used by a local long-range rifle club but the burn below is in torrent. “There’ll be little chance of crossing that safely,” Fairlie states, “though we’ll keep them in mind if the rest of the glen goes wrong.” We carry on another mile. “I hoped it would be clearer further up the glen,” Fairlie says. “We can’t see them and could waste hours walking around.” So it’s back down the glen to the roaring Falls of Unich, where Da Rosa has spotted a stag and four hinds on the steep hill below Bruntwood Craig. This day on the hill is all about teamwork. The deer offer a real possibility but Fairlie warns me that the wind swirls about here: “Many times going after hinds we have almost got in range, then the wind changes direction and spooks them.” As two of the team descend to the valley floor to keep an eye on the deer, we head up the hill. Duncan Cameron, who has been at Invermark for two seasons, has come out to help drag the stag off the hill if all goes to plan. “I moved here from Fort William for the weather and the grouse,” Cameron smiles. “It’s good news that Duncan is here,” Fairlie jokes, “as he has brought the muscles today.”

Beginning the long climb in Glen Lee

The ascent is arduous, and I haven’t put this much effort in since the Wilson Run at school (10 miles over the Cumbrian Fells). Fairlie continuously checks the wind by throwing heather. Near the brow of the rise, he murmurs: “We will be visible over the lip here.” We leave Cameron behind and continue on our hands and knees. The deer are some 300 yards away and we belly crawl to a rock 180 yards from the stag that offers a shooting position.

Victorian mountaineer William Naismith allowed an hour for every three miles travelled, and an hour for every 2,000 feet of ascent. But he did not offer calculations for a stag who decides to lie down, and this one does. In a whisper Fairlie explains that moving on will add hours we cannot afford to this task. Time is moving on and it has taken an hour to walk up the hill. All we can do is wait.

In position and waiting

The Macnab countdown ticks incessantly; it takes 30 minutes for the stag to stand, and I owe a debt of thanks to a group of walkers crossing the glen who put the hinds on alert. The stag rises to face me with his head lifted. With no chance of a broadside and the likelihood of imminent flight, Fairlie advises an immediate neck shot. I am nervous, knowing there is no time for another deer. The whole challenge rests on this shot. Taking two calming breaths, I aim and fire. The shot echoes across the valley and the stag drops.

After we find some flatter land to gralloch the six-year-old beast, Cameron joins us to drag him downhill to the waiting vehicles. Three hours spent on the hill and it is now 2pm, so no time to rest. No time to enjoy the epic scenery. No time for a leisurely piece on the hill. It is a rushed sandwich in the car to replenish reserves and a quick stop at the game larder to drop the deer off, collect a shotgun and a brace of black labradors – a mother-anddaughter team called Sage and Tweed. “No bother,” Fairlie reassures me. “We still have four hours of daylight left.”

The chosen moor is the Hill of Milton, 15 minutes east of Invermark near Tarfside. Getting out of the Hilux I am relieved to see a softly rounded, heather-clad hill. After hours climbing craggy heights in Glen Lee these gentler slopes are a more welcome prospect. They are to prove, however, just as energy sapping. I set out on point, followed by Fairlie and his dogs. Almost immediately, a covey of grouse breaks downhill. My first barrel and the shot speeds true, the grouse tumbling to the ground, but a flash of black and the appearance of an overeager labrador in my peripheral vision means I pull the second shot and the covey flees, their tails waving farewell.

We work on into the mist and rain, circling towards the summit. Sage and Tweed put up two brace to my right but I barely have the gun up before they are out of range. One grouse splits from the group and settles in the heather; however, already skittish, it rises again too far away for a shot.

Success on the hill near the Falls of Unich

After an hour here and no more action, Fairlie calls a move to the next moor. Garlet is a steep tranche of heather rising above Glen Esk and only 10 minutes away. A young Macnabber had taken his brace here two weeks before, so I am hopeful for that second bird. But after hours on hill and moor my muscles ache, and I begin pausing more often, searching an easier path over the rugged terrain. With five hours in the field, my reserves are flagging.

The first grouse

A whisper of movement is just another missed chance as a brace of grouse is lost in the rain and mist. Reaching the boundary fence at the top we immediately begin our downhill tack. Halfway down another brace rises, splitting left and right in front of me. I lift weary arms and take the righthand bird cleanly, wings folding as it falls.

A hard-won brace is finally in the bag

The chase is on. Fairlie offers effusive but brief congratulations before we set off at pace through the rain to get back on the river, with only an hour of daylight left. My elation at having finally got my brace is tempered with knowing I have to get the fish. So close but not there yet.

Fairlie has chosen two nearby pools. The first is Mark Pool, near the iconic ruin of Invermark Castle and next to the fish counting tower. The second, Monks Pool, is at the mouth of Loch Lee. Both fish better in low water, although the second can be fished in high water too. With a smaller river and water rising I move on to an 11ft switch with a sinking leader.

The stag is taken off the hill

At Mark Pool I fish quickly, letting the fly travel as advised. There is no sign, and after 20 minutes we leave for the loch. The water at Monks Pool is a canal-like channel where fish settle throughout the season. We start at the weir, and almost immediately there is a flash of silver and a salmon gently tugs on the line. My spirits soar but the fish only mouths the fly and spits it out. In the gloaming I repeat a mantra – “One more cast… just one more” – and seeing another twitch in the water, I recast to let my line drift over the spot. Hope and adrenaline surge as the fly is taken. Careful not to strike, I let the fish run before I begin to reel. But it becomes painfully obvious that this is not the salmon I so desperately want. I have landed a lovely little wild brownie just as dusk draws down.

A lovely little wild browning is a good consolation prize

This is a challenge that eludes many adventurers. I have not bagged a Macnab but a Macnot – an almost. Looking back over my day I understand the outcome takes second place to the attempt. I have chased the pinnacle of sporting achievement, enjoyed the highs of a well-placed shot and suffered the lows of a missed fish. I have carried on, determined, with my legs burning. And nothing teaches humility like taking your eye off a bird for a split second to miss a shot and adding two hours to the day. But with each step there is that sporting chance, and you kick on. Finishing with Buchan, as is fitting after such an adventure, his epithet on fishing describes the Macnab: “[it] is the pursuit of what is elusive but attainable, a perpetual series of occasions for hope”.

I am already packing for next season.

One final cast as daylight gives way to dusk

Photography by John Macpherson.